Contents

Introduction

During the first term of my M.S. in Computer Science program at Johns Hopkins, I took Foundations of Computer Architecture with Dr. Kann. He had a list of final projects that we could do, and I did one of them here. However, I also wanted to do something with a Raspberry Pi Zero W I had laying around from my previous class, so I attempted a second project, and this is the most zany but original idea I could come up with. The operative question of the day is, “can you manually tune all the parameters (weights and biases) of a neural network by hand, using hardware pieces such as some potentiometers, a few buttons, and an LCD screen?” As impractical as it might sound, the answer is yes.

Neural networks are usually trained automatically using learning algorithms on the computer. Therefore, I thought that it might be fun to manually train a network by hand using hardware inputs. In this project, I loaded several simple (2 hidden layers or less, 20 neurons or less per layer) neural nets on the Raspberry Pi Zero W and connected several hardware devices to it (potentiometer, LCD screen, buttons). I then used the potentiometer to manually tune the weights of the networks until they produced the correct output, simulating the process of training them.

Parts List

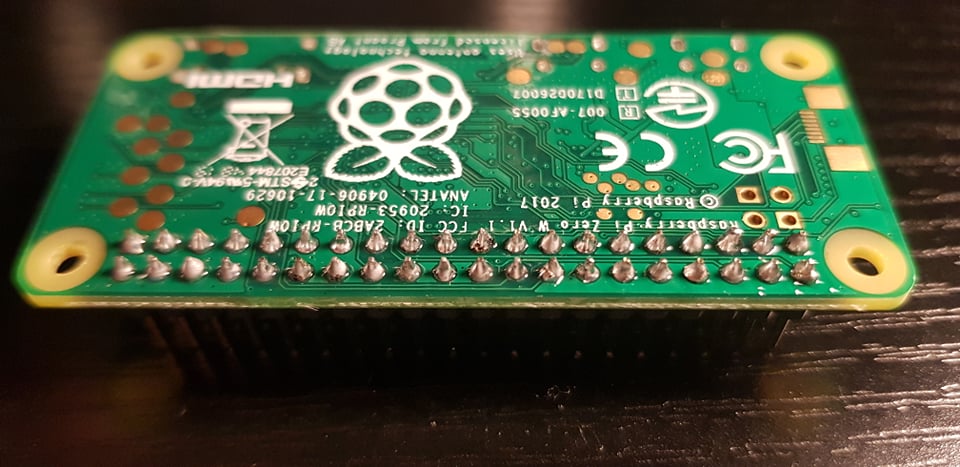

- 1 x Raspberry Pi Zero W (needs to solder GPIO pins)

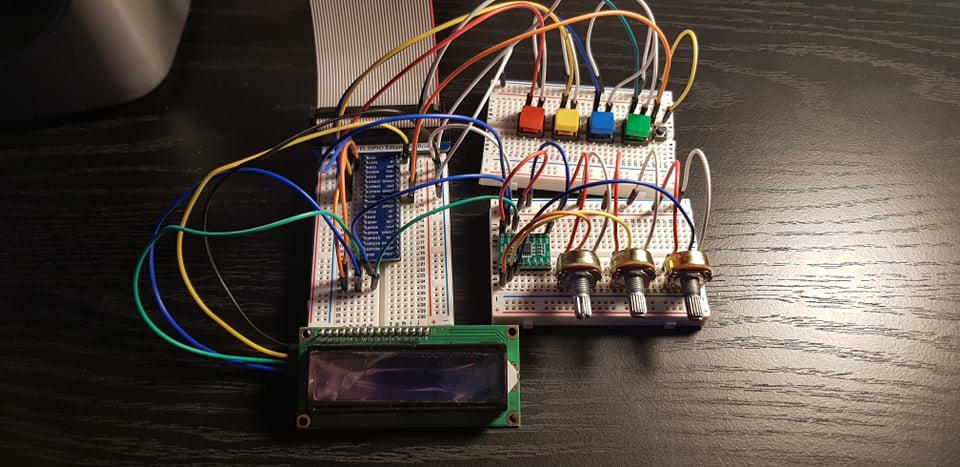

- 1 x 40 Pin GPIO Cable (optional)

- 1 x GPIO Extension Board (optional)

- 1 x I2C LCD 1602 (any display is fine, this is the one I chose)

- 3 x 10K potentiometers

- 1 x ADS7830 ADC module

- 4 x big push buttons (and caps for decoration)

- 1 x push button

- Around 40 wires

Motivation

I had several motivations for building this foolish contraption, one of which was grades. On a more serious note, I did my undergraduate in English and Applied Math at UCSB, and I think my English education contributed a lot to my ability to generate seemingly-silly questions. For my undergraduate thesis, I worked with Professor Rita Raley to think and write about forms of interacting with neural nets, which kickstarted my obsession over interesting ways that we interact with neural nets outside of bending to their prediction. Improving performance is always a natural area for research, but equally important (and fun) are the human-centric aspects of how neural nets should be interacting with us. We can think about preventive measures such as how to not make them label black men as primates, but equally important is envisioning how we should be collaborating with these thinking machines. Thus, the manual neural net hand-crank was born.

There are several applications of this tool that I can see, some of which are education and competition. First, I think that this tool can be useful for teaching undergraduates studying neural nets. The tactile feedback that one gets from manually tuning a network and re-tuning it as needed until a satisfactory result is returned can greatly contribute to the learning process. In fact, although it took me around 14 minutes to manually tune a network to act as a NAND gate, the process of fiddling with the weights, checking the outputs, and correcting them until the network was correct gave me a fresh perspective on how these networks are trained. Moreover, would it not be fascinating to see deep learning competitions of teams trying to manually tune a 1 trillion parameter language model? I am kidding, of course, as I cannot see practical applications for a manual tuner for a network of that size, other than the fact that it would be quite amazing to see a machine with 1 trillion dials designed to tune a 1 trillion parameter language model. Going back to the small scale, however, there might be insights that can come from an alternative way of looking at and handling neural nets (check out Neural Networks in Desmos ). I know that I learned a lot of intuition about neural nets by watching videos that included visualizations. Therefore, my neural net hardware tuner is an alternative way of interacting with neural nets. It is time to take back control from the machines, and I know of no way better than to tune a billion weights by hand.

Background

Read Deep Learning.

The Build

I began the build by soldering the 40 GPIO pin headers to my RPi board. This was a learning process in and of itself, and these are the resources that helped me (e.g. [1][2][3][4]). I bought a cheap soldering kit on Amazon and went to work, and the result was satisfactory.

To get the creative juices flowing, I bought one of those starter kits on Amazon that includes a bunch of hardware that you can test out on the RPi. I spent some time learning about the different sensors and hardware components that can interact with the RPi. I really liked handling the potentiometer, because turning the smooth dial gave me an indescribable sense of satisfaction. I believe it was at this point that I thought about the idea of using potentiometers to tune a neural net, but the idea seemed so stupid I completely dismissed it. I came up with and tested a lot of other ideas that were unoriginal, as so many of them have already been accomplished (much better) by the RPi community: smart glasses, real-time image captioning, smart groceries list, emotion detector (a la the Deus Ex games). As the deadline for the final project fast approached, I crawled back to my neural net hand-crank idea out of desperation.

I first set up the potentiometers to get a feel for how I can get their inputs. If you buy the exact same RPi starter kit as me, then I highly recommend this video for learning how to set up the potentiometers. I set up three potentiometers because there were three potentiometers in the kit. If I had more, I would have set up more (given the ridiculous amount of parameters in the larger networks). I connected these potentiometers to the included ADC module because my RPi does not have analog input. The ADC module converts the analog signals from the potentiometers into digital signals (from 0 - 255), and thus I was able to get the position of the potentiometers.

The next step was setting up the I2C LCD screen, which I intend to display information about the current weight or bias that the user is tuning. Note that LCD screens come in a lot of different flavors, so it is important to figure out which one you have. The one that came with my kit had an I2C backpack that could interface directly with the RPi using I2C. I used these guides (e.g. [5][6]) to set up this part. It was really hard at first because nothing was displaying on my screen, and this is where I learned about a little setting known as “Contrast”. I used the RPLCD library for Python to control my LCD.

The next component I set up was the buttons, which is intended to be used for navigating through the different layers and weights of the neural net. I originally went with the joystick that was included in the kit, but it was unintuitive. Thus, I resorted to emulating a keypad with four buttons. The first two would be for hopping between the different layers of the neural net, and the other two would be for looping through the weights of a layer. I also included a fifth button at the end (whose purpose I will detail later). I would have laid the buttons in a cross shape like on a D-pad but that configuration did not fit my breadboard (or I am just a noob at electronics), so I just laid them side by side. Here’s the guide that I followed for setting up buttons on the RPi.

With the hardware all set up, the next step was the software, which was by far the most tricky part. I needed to implement a neural net from scratch, and keras, with its ability to allow users to examine the weights of a network, seemed promising. However, I eventually landed on James Loy’s custom implementation of a neural net using nothing more than numpy. This gave me more control on the parts of a neural net that I actually want. Since this project intends to tune a neural net by hand, I did not implement backpropagation or any sort of training method (I totally get backpropagation I swear). I extended James Loy’s example to allow for the creation of more than just a fixed neural net. With my code, users can instantiate the NeuralNetwork class and specify the number of hidden layers and the number of neurons per layer that they want to create. The NeuralNetwork class has the standard feedforward and predict methods, but of more importance are the methods that get and set the weights and biases of the networks. Since the weights and biases are implemented as numpy arrays, getting and setting them were as easy as accessing an array. I think this greatly demystifies the scary mental image of neural nets that a lot of people have. They are just collections of numbers, folks.

To stress test my neural net, I followed a guide on coding a network that can add two numbers using Keras. This network has two hidden layers, each of which has 20 neurons. I downloaded the code from the guide, trained the included network, and copied the weights and biases of the network over to my custom network. The translation process was surprisingly straightforward, and since we were (coincidentally) both using ReLU as our activation function, I was able to “manually” train my custom neural net to add two numbers. Then, the next step was to tie this training process to hardware.

The marriage of software and hardware was largely dependent on accessing and displaying the correct weight and bias of the network. To start, I wrote a while loop that continuously monitored my buttons and potentiometer for change. If a button is pressed, then we either move through the layers of the network or the weights of a specific layer. If a potentiometer is turned, then one of three things are happening. If the first potentiometer is turned, then we adjust the value of the weight we are currently viewing. The second potentiometer is reserved exclusively for the tuning of the biases of a layer. When these potentiometers are turned, an update weight or update bias function is called and the weights and biases of our network are changed. The third potentiometer is used to switch between tuning weights and biases, i.e. if the potentiometer is turned left of a specified halfway value, the code knows we want to tune weights, and if the potentiometer is turned right of the halfway point, the code knows we want to tune biases.

With this main logic settled, the next and final step was to enclose it in an outer while loop that can handle inputs and prediction. Thus, I wrote a while loop that takes in user commands to either tune the network or use it for prediction. Typing in “prediction” will allow you to test out the network’s prediction on a certain input that you feed the network. If the result was unsatisfactory, you can type “tune” and change the weights and biases and check again to see if the prediction was better. This loop is the crux of my simulation of the training of a neural net. Typing “q” will quit the program, which is what I will be doing to this section.

Demo

Negation

We start the demo with a simple network with one hidden layer and one neuron. The objective of this network is to return the negation of a number. So the network should return -1 if the input were 1.

This network is simple enough for us to tune by hand. Given what we know about the mathematical representation of a neural net, taking into account the effects of activation functions (we chose ReLU for this one), it seems like the obvious answer is to set the weight from the input to the hidden layer as 1 and the bias as 0. Then, setting the weight from the hidden layer to the output as -1 should give us the desired result.

XOR

| X1 | X2 | X1 XOR X2 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

Next, we kick it up a notch by manually training a neural net to compute the XOR operation (See Figure 6). We will use the network presented in the Deep Learning textbook that has one hidden layer with two neurons (See Figure 7). We will be tuning the weights and biases of each layer, represented graphically in Figure 7 by the directed edges between each node. The textbook actually provides the solution set of weights and biases, which we can use to tune the network. Although this defeats the purpose and fun of the project, we can proceed in this fashion to verify that our software and hardware implementation is correct. In Figure 7, W denotes the set of weights going from the input layer to the hidden layer, w denotes the set of weights from the hidden layer to the output layer, and c represents the bias added in the hidden layer.

We first randomly initialize a network and test its performance against the input. As expected, the network is not able to produce the correct answers. The outputs of the untrained network are XOR(0,0) = 1.37, XOR(0,1) = 2.03, XOR(1,0) = 2.42, and XOR(1,1) = 3.09. We then tune the network using our neural net hand-crank. The process is lengthy, but ultimate rewarding when we get the right answer. The outputs of the trained network are XOR(0,0) = 0.00, XOR(0,1) = 1.02, XOR(1,0) = 1.00, and XOR(1,1) = -0.03. Notice that the answers are not completely correct, but it gets us closer to the actual answers than when we started, suggesting improvement with training.

NAND

| X1 | X2 | X1 NAND X2 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

At the advice of Dr. Kann, I picked the NAND gate as the final proof of concept for my contraption, due to the fact that any Boolean expression can be represented solely by NAND gates [7]. This way, he said, I can claim that my contraption is a universal computing unit. I went in blind, and attempted to tune the network without any prior knowledge of the solution set of weights and biases. I first decided that the network should be similar to the one used for my XOR example, given how close the two functions are in terms of output (they only differ in the output for (0,0)). Thus, I instantiated a network with one hidden layer with two neurons, and I entered the same weights that were used for the XOR network. As expected, this produced XOR outputs but not NAND outputs. For the next 14 minutes, I manually tweaked each weight and each bias of each layer to figure out the effect that each one was having on the output. I cannot say I remember which weights are responsible for what (I should have written it down), but there was a point when the whole process clicked when I found the one weight that, when held constant, gave me the output that I needed. It was like solving a sudoku puzzle through an iterative process of trial and error. I cannot describe the amount of euphoria I felt when I isolated that one weight that made everything worked. The final outputs of the network are NAND(0,0) = 1.03, NAND(0,1) = 1.01, NAND(1,0) = 1.08, and NAND(1,1) = -0.12. I could have kept tuning the network until the -0.12 went away, but I stopped because I had better things to do than to tune a network for more than 15 minutes. Shouldn't computers be doing this?

Conclusion

I had an absolute blast doing this project. From learning how to solder to making something so stupid it’s brilliant, this was an incredibly rewarding experience for me. I think my biggest takeaway is the experience of emulating how neural nets are trained. I was able to experience firsthand the iterative cycle of feedforward and “backpropagating" the errors to fix the weights until something worked. In addition, the aha moment one gets when you find the one weight responsible for making the whole network work is incredibly satisfying and illuminating. Although the act of taking it slow and analyzing networks at a micro scale in an age of deep learning parameter arms race can be considered heretical, I think my project proves that this is an area for potential further research.

There are several natural next steps for this project, all of which I encourage the RPi community to go crazy with. The first obvious improvement is to add more hardware pieces and to try out different inputs. Perhaps there is an input device out there that is more intuitive than a potentiometer or a button. In addition, I will definitely revise the visualization aspect of my project. Displaying the weights one by one on a 16x2 LCD screen seemed fun at first, but it quickly became unintuitive when it would have been helpful to see the network as a whole. A GUI that shows the whole network as you are tuning it would definitely improve the learning experience.

Related to the points above is the expansion of this tool to teach more complex concepts and network architecture. The most obvious concept that I completely omitted was backpropagation, an essential component that was responsible for neural nets' mainstream success. How do we teach backpropagation using this tool, so that students can manually tune the network with some sort of intuition rather than going at it blind like me? Do we give them pen and paper so that they can calculate the exact errors needed to backpropagate through the network?

It would also be interesting to see this tool (and its better iterations) applied to bigger and more complex networks. Try it on convolutional networks and my favorite network, the Transformer! In fact, this tool is currently compatible with any standard fully-connected feedforward network. I actually have a camera connected to my RPi, and I can see a self-contained image recognition network loaded onto the RPi, manually tuned by my contraption and getting input from the camera. Perhaps someone would be brave enough to use my tool to tune a network for MNIST? I think that a step in achieving this goal would be to make the code more flexible and scalable. I think it would be helpful to turn the code into a libary that serves as the interface between neural networks and hardware input devices. You should be able to specify the architecture of your network and the type of hardware inputs you are hooking it up to and the library should automatically generate the correct linkages to get and set weights and biases.

Also, if you are reading this sentence, then I probably have not refactored my code, so that is another area that needs work.

© 2023 Minh Hua